Spots on My Back With Weird Texture and Feel

What is it like to have never felt an emotion?

(Image credit:

Getty Images

)

Some people seem to lack the capacity to feel joy, sorrow or love. David Robson discovers the challenges and surprising advantages of "alexithymia".

C

Caleb is telling me about the birth of his son, now eight months old. "You know you hear parents say that the first time they looked at their kid, they were overcome with that feeling of joy and affection?" he asks me, before pausing. "I didn't experience any of that."

His wedding day was equally flat. To illustrate his point, he compares it to a Broadway show. In front of the stage, he says, the audience are transported by the drama. Look behind the scenes, however, and you will find the technical engineers, focusing on analysing the technicalities of the event.

Despite taking centre stage at the ceremony, he felt similarly detached from the tides of emotion swelling up in the people around him. "For me, it was a mechanical production," says Caleb (who asked us not to use his full name). Even as his wife walked down the aisle, the only sensation he felt was his face flushing and a heaviness in his feet; his mind was completely clear of joy, happiness, or love in its conventional sense.

In fact, Caleb claims not to feel almost any emotions – good, or bad. I meet him through an internet forum for people with "alexithymia" – a kind of emotional "colour-blindness" that prevents them from perceiving or expressing the many shades of feeling that normally embellish our lives. The condition is found in around 50% of people with autism, but many "alexes" (as they call themselves) such as Caleb do not show any other autistic traits such as compulsive or repetitive behaviour.

When you struggle to feel any emotions yourself, others' behaviour can seem alien to you (Credit: Getty Images)

Getting to the bottom of this emotional blindness could shed light on many serious illnesses, from anorexia and schizophrenia to chronic pain and irritable bowel syndrome. More personally, stories from the "alex community" lead you to re-examine experiences that you might think you know so well. How can you fall in love, for example, when you lack all the basic tender feelings of affection that normally spark a romance?

Shells of feeling

To understand that emotional numbness, it helps to imagine emotions as a kind of Russian doll, formed of different shells, each one becoming more intricate. At the heart is a bodily sensation – the skip in your heart when you see the person you love, or the churning stomach that comes with anger. The brain may then attach a value to those feelings – you know if it is good or bad, and if that feeling is strong, or weak; the amorphous sensations begin to take a shape and form a conscious representation of an emotion. The feelings can be nuanced, perhaps blending different types of emotions, such as bitter-sweet sorrow, and eventually we attach words to them – you can describe your despair, or your joy, and you can explain how you came to feel that way.

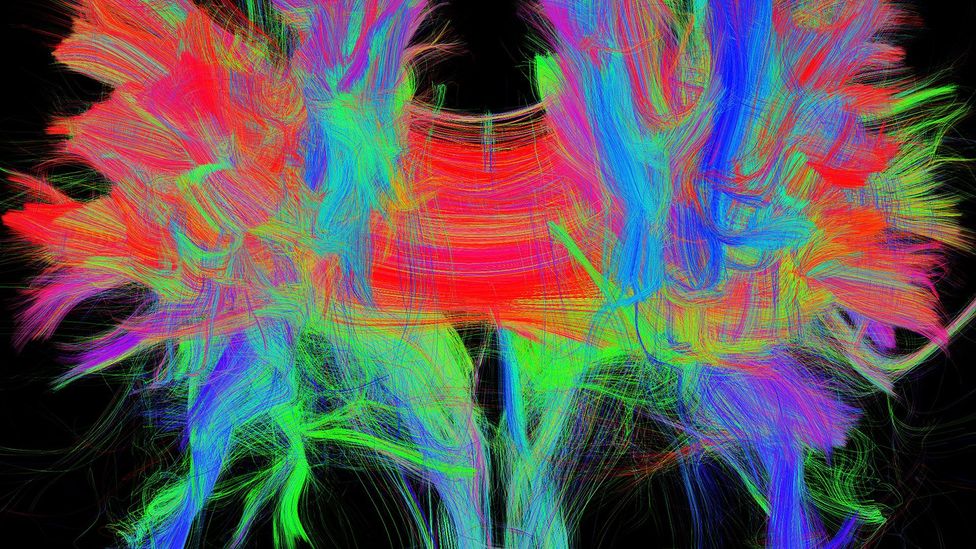

When alexithymia was first described in 1972, the problem was thought to centre on this last, linguistic stage: deep down people with alexithymia felt the same as everyone else, but they just couldn't put the emotions into words. The scientists hypothesised that this may result from a breakdown in communication between the two hemispheres, preventing signals from the emotional regions, predominantly in the right, from reaching the language areas, predominantly in the left. "You need that emotional transfer in order to verbalise what you're feeling," says Katharina Goerlich-Dobre at RWTH Aachen University. This could be seen, most dramatically, when surgeons tried to cure epilepsy by cutting the fibres that connect the two hemispheres; although it reduced the seizures, the patients also appeared emotionally mute as a result. Less sensationally, Goerlich-Dobre's brain scans have found that other people with alexithymia seem to have abnormally dense connections in that neural bridge. This might create a noisy signal (a bit like a badly tuned radio) that prevents emotional cross-talk, she thinks.

When surgeons cut the dense connections between the two hemispheres, patients become emotionally mute and unable to express their feelings (Credit: Science Photo Library)

Today, it seems clear that there may be many types of alexithymia. While some might have trouble expressing emotions, others (like Caleb) might not even be conscious of the feelings in the first place. Richard Lane, at the University of Arizona compares it to people who have gone blind after damage to the visual cortex; despite having healthy eyes, they can't see the images. In the same way, a damaged neural circuit involved in emotional processing might prevent sadness, happiness or anger from bursting into consciousness. (Using the analogy of the Russian doll, their emotions are breaking down at the second shell of feeling – their bodies are reacting normally, but the sensations don't merge to form an emotional thought or feeling.) "Maybe the emotion gets activated, you even have the bodily responses, but it happens without you being consciously aware of the emotion," he says.

Along these lines, a few recent fMRI scanning studies have found signs of a more basic perceptual problem in some types of alexithymia. Goerlich-Dobre, for instance, found reduced grey matter in areas of the cingulate cortex serving self-awareness, potentially blocking a conscious representation of the emotions. And André Aleman at the University Medical Centre in Groningen, the Netherlands, detected some deficits in areas associated with attention when alexithymics look at emotionally charged-pictures; it was as if their brains just weren't registering the feelings. "I think this fits quite well with [Lane's] theory," says Aleman – who had initially suspected other causes. "We have to admit they are right."

Caleb himself describes a "conscious disconnect" that prevents emotions from breaking through into his mind. For instance, one day at school he was working with the student theatre. All week he had been struggling to produce the right sound effects, but it just wasn't coming together. Eventually, his boss lost his cool and started ripping into him. "My response was that something weird was happening with my body," he says. "I could feel a tension, like my heart was racing, but my mind was distracted… It was an academic curiosity, and then I completely forgot about the whole situation," he says. It seems that almost no event can penetrate that indifference. "The more extreme the emotion I should be feeling, the more it should be colouring how I'm thinking. In reality I end up having a clearer head – I become more analytical."

Contrary to the stereotype, autistic people do not all suffer emotional or social difficulties (Credit: Science Photo Library)

There is one, slim advantage: he finds it easier to cope with medical procedures, since he doesn't attach the fear, sadness or anxiety to it. "I can put up with an awful lot of pain or unpleasant experiences because I know very shortly I won't have an emotional memory associated with it," he says. "But it means that positive memories get washed away too."

Neural short circuit

It is a small pay-off, however: alexithymia seems to be linked to various other illnesses, including schizophrenia and eating disorders, perhaps because emotions normally guide us to take better care of our physical and mental health. Better defining alexithymia could therefore offer insights into these disorders. It could also give us a more nuanced understanding of autism. Despite the stereotypes, Geoffrey Bird at Kings College London points out that around half of autistic people are perfectly capable of perceiving and responding to others, and those with social problems tend to also be suffering from alexithymia. For this reason, he thinks that distinguishing the two, distinct, disorders could therefore lead to better guidance. At the moment, misunderstandings can often stand in the way of some autistic people getting the help they need. "One autistic adult I worked with wanted to be a carer, but she was told 'you don't have empathy so can't have the job'," he says. "Our research shows that lots of people with autism are fully okay with emotions."

Further work could also pin down the puzzling link to so-called "somatic disorders", such as chronic pain and irritable bowel syndrome, that seem to be unusually common in people with alexithymia. Lane suggests it's down to a kind of "short-circuit" in the brain, created by the emotional blindness. Normally, he says, the conscious perception of emotions can help damp down the physical sensations associated with the feeling. "If you can consciously process and allow the feeling to evolve – if you engage the frontal areas of the brain, you recruit mechanisms that have a top down, modulatory effect on bodily processes," says Lane. Without the emotional outlet, however, the mind could get stuck on the physical feelings, potentially amplifying the responses. As Goerlich-Dobre puts it: "They are hypersensitive to bodily perceptions, and not able to focus on anything else, which might be one reason why they develop chronic pain." (Some studies, have in fact found that alexes are often abnormally sensitive to bodily sensations, although other experiments have found conflicting evidence.)

People with alexithymia often travel a lonely road as they try to connect to their emotions (Credit: Getty Images)

Physical sensations certainly seem to dominate Caleb's descriptions of difficult events, such as periods of separation from his family. "I don't miss people, as far as I can tell. If I'm gone, and don't see someone for a long period, it's a case of out of sight, out of mind," he says. "But I do feel physically a kind of pressure or stress when I'm not around my wife or my child for a couple of days."

Reconnecting to lost feelings

The hope is that eventually, doctors may be able to track down the origins of alexithymia and stop the effects from snow-balling. Caleb thinks his alexithymia emerged at birth and could be genetic. Upbringing – and the emotional fluency of your parents – may also play a role, while for others, it may be caused by trauma that shuts down people's ability to process some or all of their emotions.

Lane, for instance, introduced me to one of his patients, Patrick Dust, who was the subject of violent abuse from his alcoholic father – experiences that put his life in danger. "One night, when he came home, my mother and he had another intense verbal argument. He said 'I'm going to get my shotgun and kill all of you'… We ran to a neighbour's house where we called the police." For decades afterwards, he found it difficult to interpret and understand his emotions, particularly the fear and the anger he still felt towards his parents. He suspects this resulted in his fibromyalgia – chronic diffuse pain and tenderness across the whole body – and an eating disorder.

With initial guidance from Lane and later by himself, Dust was able to revisit the past and reconnect to the emotions he was locking away, which he thinks also brought some relief to the fibromyalgia. "I discovered the tremendous anger I had felt, without much awareness of it," he explains. "It's the most important thing I've done in my life." He has just finished writing a book about the process.

By making a conscious effort to love, alexithymic people may offer stability in a relationship (Credit: Getty Images)

Caleb, too, has visited a cognitive behavioural therapist to help with his social understanding, and through conscious effort he is now better able to analyse the physical feelings and to equate it with emotions that other people may feel. Although it remains a somewhat academic exercise, the process helps him to try to grasp his wife's feelings and to see why she acts the way she does.

Not everyone with alexithymia may have his determination and patience, however. Nor may they find a life partner who is willing to make the allowances his condition requires. "It takes a lot of understanding on my wife's part… She understands that my conceptions of things like love are a bit different," he says. In return, she may benefit from his stability – he is not swayed by the fickle tides of feelings. "The trade-off is that my relationship with my wife is a conscious choice," he says – he is not acting on a whim but a very deliberate decision to care for her. That has been particularly helpful in the last eight months. "It means that if we're going through a difficult situation – if the kid's up all night crying – for me that doesn't affect our relationship at all, because the connection isn't built on emotion," says Caleb.

Caleb may not have been transported to ecstasy by his wedding or the birth of his child, but he has spent most of his life looking within, striving to feel and understand the sensations of himself and the people around him. The result is that he is certainly one of the most thoughtful, and self-aware, people I have ever had the pleasure of interviewing – someone who seems to know himself, and his limitations, inside out.

Ultimately, he wants to emphasise that emotional blindness does not make one unkind, or selfish. "It may be hard to believe, but it is possible for someone to be cut off completely from the emotions and imagination that are such a big part of what makes us humans," he says. "And that a person can be cut off from emotions without being heartless, or a psychopath."

David Robson is BBC Future's feature writer. He is @d_a_robson on Twitter.

Follow BBC Future on Facebook , Twitter , Google+ and LinkedIn .

Spots on My Back With Weird Texture and Feel

Source: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20150818-what-is-it-like-to-have-never-felt-an-emotion

0 Response to "Spots on My Back With Weird Texture and Feel"

Post a Comment